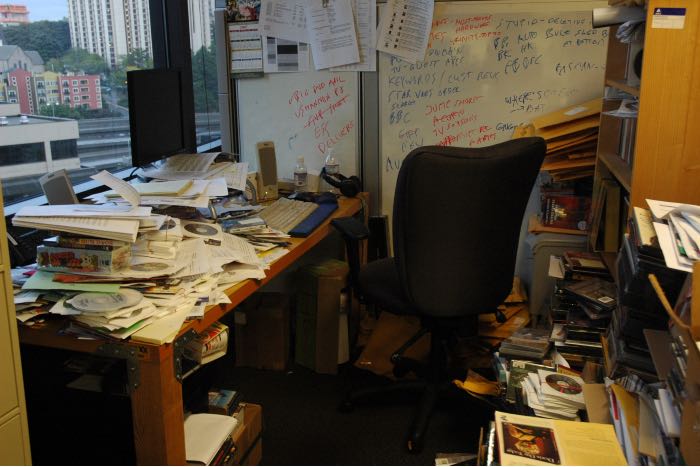

Messiness is, of course, what we’re taught to avoid.

Logic is linear. And precise. A begets B and then C. Do your work. And show it.

Expertise is developed through hard work and perseverance. And yet brilliant discoveries come in bursts and unlikely places, far removed from determined time.

Famously, on walks. Or in the shower. Insight blazes when we aren’t pouring over the data or working from step to step.

Brilliance comes, not from linear discovery, but adjacent discovery. Not from connecting the most obvious dots but ones nobody else would.

Our bias against messy thinking is doing us harm.

We can look no further than our experience of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Our Logic Problem

It is quite simple, on the face of it.

- Conspiracy theories develop in precise, linear fashion.

- Active scientific discovery appears messy and imprecise.

And perhaps the most damaging aspect of the public pandemic (aside from the virus itself) is that the public health community spent more time on the definition of “airborne” than on observing what the virus was doing.

The origin of both intentional misinformation and wrong information about the virus, stemmed, not from messy thinking, but established, logical thinking.

This coronavirus couldn’t be airborne, they argued, because airborne transmission is different. Therefore, we probably don’t need to follow airborne protocols.

Except that it is airborne and we should have.

They came to this conclusion because the definition of “airborne” is faulty. And all of the assumptions that stem from declaring something is airborne or not guide countless downstream decisions.

But don’t call it a wrong decision.

Based on the definition, they were making the right decision. The definition itself is bad.

Then we follow all that flows from the original decision.

Again, doing all of that is the right thing to do. Except that this all was the wrong way to treat this virus.

We trusted the wrong impulse.

In a very real sense, it was doing the logical thing that led to public harm. Trusting it over the evidence in front of us led to bad public health decisions. And worse, it was the fuel for misinformation.

Not because it was messy, but because it was eminently logical.

It is messy thinking, the kind that notices, changes, and focuses on what is needed in the moment, that did far more good throughout the pandemic. Not because it lacks logic, but because it is far more aware of adaptation and discovery.

This is a novel virus, after all. Conventional logic about novel things should have prepared us for novel and messy thinking, not the opposite.

Scientists, doctors, and academics who could see beyond the logic saved countless lives.

And chances are, they have messier desks, too.