There’s a phrase that seems sensible. We say that elections have consequences, which is, I think, intending to suggest that this is the result. Whatever this is. It comes from that. That we had an election.

For some, this is a comforting idea, I suspect. Especially for the thoughtful many who think every thing is a direct result from a previous thing. And that certainly is how butterfly wings lead to tsunamis, but we so rarely suggest the two are so directly related — and only in science fiction stories about time travel. The rest of the time, we ought to recognize a natural distance between things. One butterfly here [stuff stuff stuff] tsunami there. Most of the time all of that stuff in the middle amounts to a lot more than nameless nothing.

This isn’t to say results and origins aren’t important, right? But that other stuff is also. That stuff that’s too often left unsaid, unrecorded, unrecognized.

But is it even true?

One of the other hinderances to the elections have consequences response to US politics is that it frequently seems to be patently untrue. We elect one person to office and the personal impact seems imperceptible. Most of the time. Assuming the person elected hasn’t targeted your humanity or considers you a personal rival.

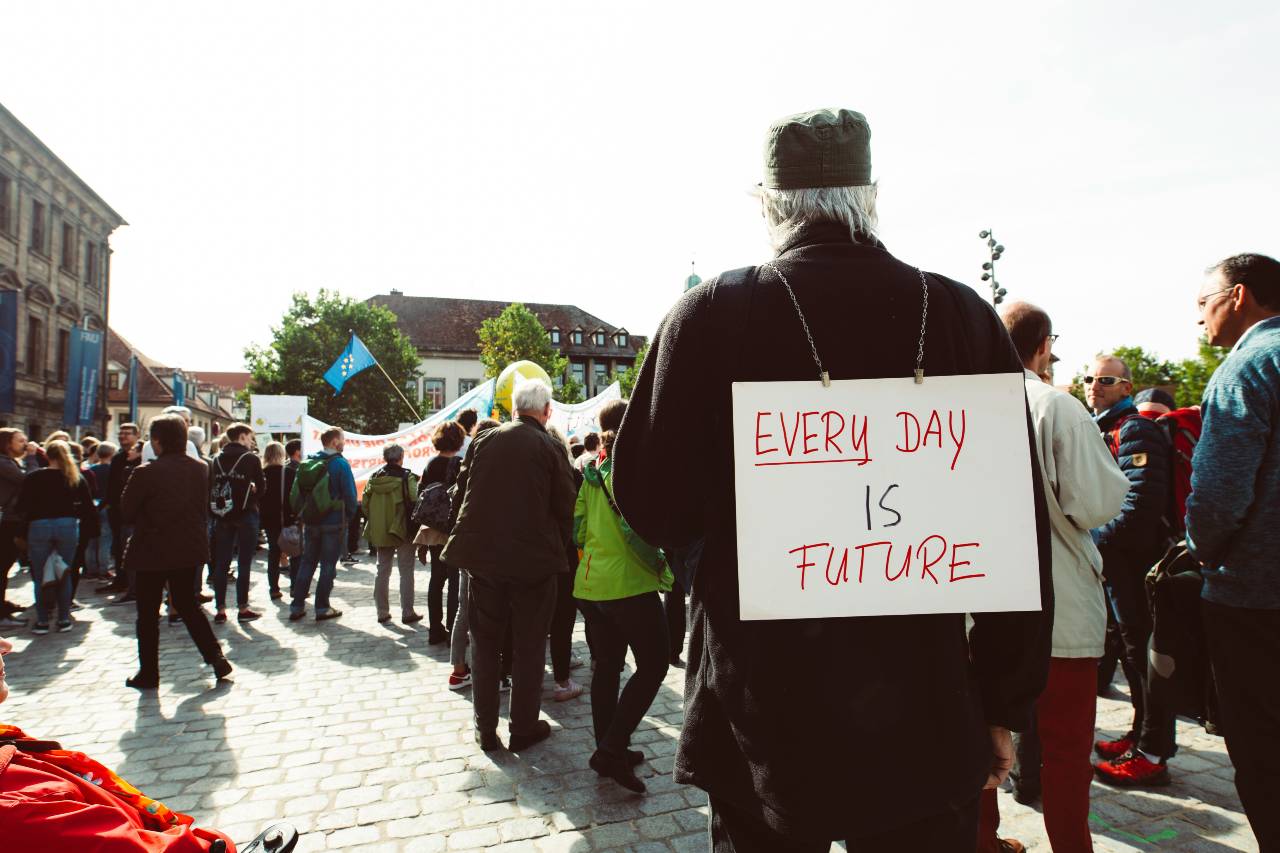

Most of the time, we are allowed to go about our business like elections decidedly don’t have consequences. And that is part of what they sold us in the 1990s. And why some of the people marching a few weeks ago had signs that said “I’d rather be at brunch right now”. It is a demonstration of just how many have internalized the idea that elections should have few consequences, actually. This, too, is dumb.

More significant, however, is the suggestion that elections won’t have consequences. Primarily because our elected officials don’t intend to listen to us even a little bit. A 2014 Princeton University study found that economic elites and business interests have significant influence on legislators while the impact of average citizens and interest groups is near-zero. In this sense, elections and consequences seem distinctly unrelated.

How other countries do it

The US isn’t the only democratically-aligned country. One of the obvious differences between our republican system and the parliamentary systems other countries use is that in other systems, the election winners form the government. In these systems, elections actually matter because the majority gets to govern — and the people live with the consequences. In the US, the minority can more vociferously obstruct and prevent, leading, in theory, to more compromise.

Like many others, I’ve often speculated on what it would mean if the minority party simply let the majority have its way. They won the election, so they get to govern for the next two years. Good luck! This does feel more democratic, doesn’t it? It is, as we like to say, “the will of the people” after all. And I suppose it is.

Should we consider it? To go ahead and let elections have such steep consequences?

What these thoughts rarely consider, however, is how we’re trained, not for democracy, but for obstruction. Our civic conversation often couches this in the terms of rights and an intentional system of checks on power. From the electoral college to the senate to the filibuster to the founders’ concern with discriminating the land-owner from the public — we have a long history of undemocratic influences compromising our systems, tempering them, not just from tyranny, but also from equality. We see a kind of virtue in obstruction, rather than focus on what our laws more directly empower, which is centrist homogeneity.

Separate and Unequal

The popular phrasing reveals much: majority rule, minority rights. And its prime example is found in the battlefield of civil and equal rights. Rights were won, not through the supposed democratic character of our institutions, nor in the famously-regarded counter-argument to majority rule that is minority rights, but in the spilling of blood in our streets and on bridges. It was the dramatic change in heart of the masses and the willingness of courts to finally do the right thing. It came from changing the narrative enough to change the laws themselves. And, no less importantly, those enforcing the laws.

The whole system needed to change.

When the politically-savvy presently pontificate about the need for checks on the power of tyrants, now more than ever, they speak constantly, not of people, but of institutions. The courts. Congress. Or they speak of anthropomorphized abstractions: something we call the rule of law. And so we protect the filibuster because it is the only action to keep the tyrant in check. Yet, also, there are “the courts”. There is little spoken in these places about the power of people or in local municipalities. No actual expressions of democracy — only obstruction and denial.

Brilliant minds wonder how this can happen here. And without any hint of irony . . . or self-awareness. And they do so while also wondering how less democratic countries beat the United States to equality and more democratic governments. It seems even the most conservative and illiberal countries have found a way to elect a woman as prime minister or administer cheaper healthcare to all of its people. They better educated their citizenry, keep them healthy, and live longer. Heck, in most of these places, they even rate much happier.

And yet we shrug, regurgitating the claim that it’s impossible here. We’re not ready.

Power

It seems that there is an inverse relationship to US expectations of elections and consequences. Those places in which the true fate of a decision falls upon the people who win elections often have more democracy — and stability. Even when Canada calls for a snap election, for example, party leaders run for a few weeks, the public makes a decision on, and the government goes with it.

Ours, from this perspective, engineers a far less stable transition of power. In fact, we are in a perpetual election cycle at incredible expense, leading to the least efficient government on the planet. And none of this accounts for the ever-present lionization of gridlock and the purposeful slowing of progress.

If we adopted the total consequences mindset today, would it work? Without also adopting the systems which protect people from those consequences, I doubt we’d see much success. Shall we allow a tyrant to starve the public for two whole years? Ah! But we do have a mechanism to deal with such a situation: impeachment!

Oh. I see the problem.

“Oh, but we’ve tried that,” we’ll say. And not realize that our refusal to use our own mechanisms proves the point.

The Centrist Mindset

We must acknowledge how much we’ve been taught to believe in obstructive centrism. That it is a neutral good in itself. That it is more than a check on power, but its own power. It is a polarizing power, which changes the game from a competition between one extreme and another, it recasts the battle as a battle between extremes vs. moderates. Obstructive centrism holds itself as better, more rational, than any single ideology. An apex ideology.

This is why we need a single person to gum up the works — not of business for the sake of the workers, but government for the sake of political gridlock. And for the sake of tax breaks for billionaires or cornhusker kickbacks. You know, the stuff of compromise.

Comfortable Injustice

It strikes me that the less our elections are supposed to have consequences, the more comfortable we get in present injustice. In our being taken advantage of and accepting the unacceptable. Even more so, when given our present fears. That a tyrant can come in and ignore the anthropomorphized abstractions while the human beings with actual systemic power seem frozen to their seats. We anticipate the checks can just happen. And we can just keep on going.

So we can see in the wheels of government these deficiencies and wonder why they happen and still not realize how to fix them. That a president can ignore the Supreme Court. And congress. And the constitution, the rule of law, governors, mayors . . . And we can see the downside of two branches of government having invested zero dollars or hours investing in a means of protecting their authority.

In short, we’ve championed a system of checks and balances as more democratic and we haven’t bothered to make any of it real. No material investment in checking or balancing. No people or even systems of enforcement. Not for the courts or congress.

We aren’t seeing the mere consequence of an election. This is the abdication of the responsibilities of millions of Americans to protect the constitution from tyranny.

And not one bit of this relates to the ballyhooed checks and balances inherent to the US system. Much the opposite. The system which seems perpetually frightened to make new precedents on purpose allows new precedents to stand constantly. Not because we want elections to matter, but because the modern interpretation of the constitution makes us think they shouldn’t.

In all of our fear of tyrants, we have allowed the one vehicle we have to dispose of them — the power of the people — to atrophy. And this seems the least democratic outcome of all.