This Week: Palm & Passion C

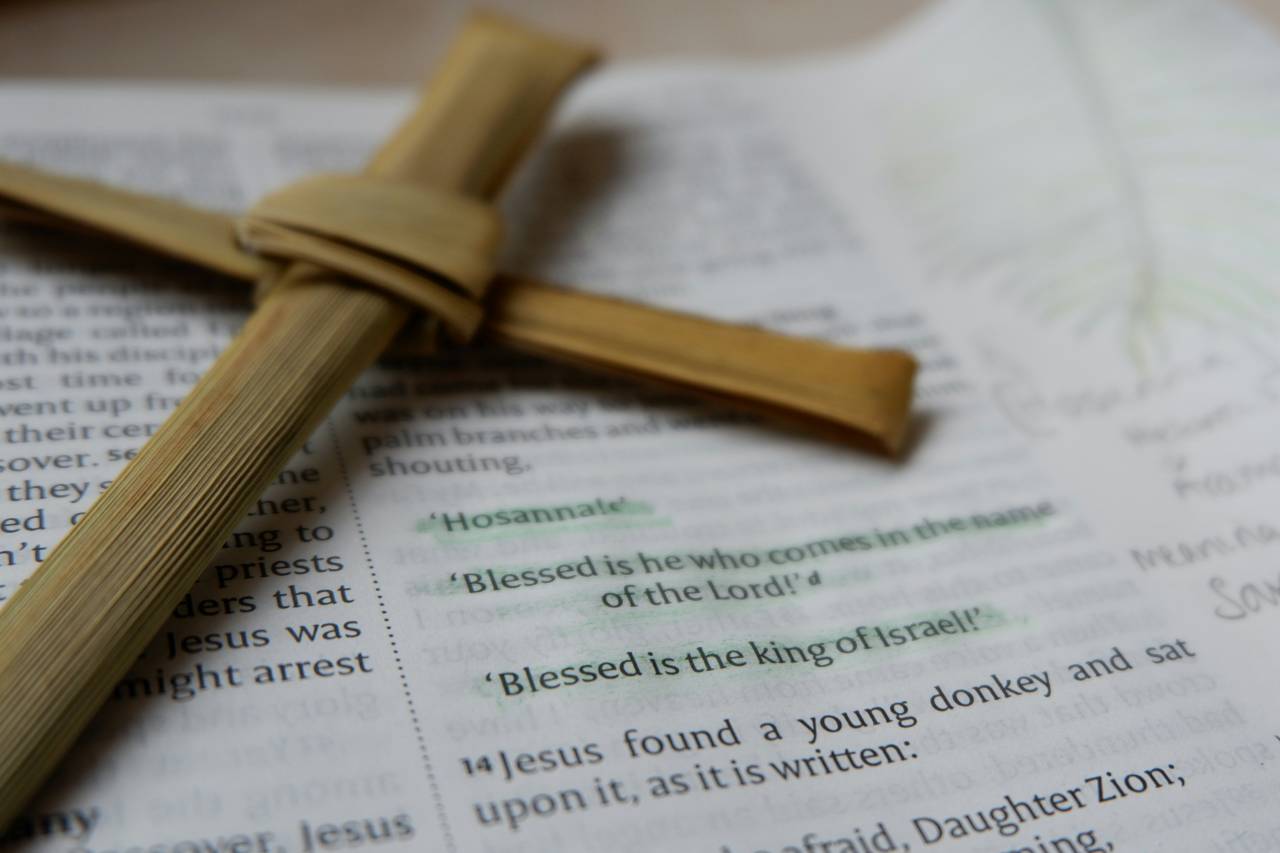

Gospel: Luke 19:28-40

The persistent interest of Jesus’s ministry is the revelation of power. How humans wield it to oppress one another. And how God uses it to heal, restore, and give birth to new creation. The juxtaposition of the tyranny of humanity against the goodness of God is a regular theme in Jesus’s teachings. It is so clearly revealed in these moments of deep contrast.

The story of the triumphal entry and then the quick liturgical move to the Passion causes a kind of existential whiplash that often serves as an emotional rejection of the moment or perhaps worse, an emotional separation from the evil of execution as if it were the “good” that God is intending. The proverbial egg that has to be cracked to make the divine omelet.

Why it’s difficult

I’ve often found the church quite cowardly in its refusal to face what our tradition has begot around this week. Between the rampant, historic antisemitism that surrounds our traditional approach to it, the tepid interest in saying anything about Jesus’s critique of power, and our entirely emotional and spiritual approach to a season in which our Messiah was physically killed by the state as a terrorist. A truth so few Christians are challenged to accept has a direct relationship with their own political interests.

I have become quite resistant in recent days to the over-spiritualizing of our faith tradition — to the exclusion of real world corollaries. There is a moral disconnect from a tradition that preaches peace and sponsors crusades. And that disconnect doesn’t simply come from “seeing things differently.” When peace is the main platform, justifying war of any kind comes, not from a different way of seeing, but from making excuses for rejecting the prime directive.

But here, dear reader, I merely want to offer some meager suggestions for how we might approach this big, difficult holy day.

If we focus on the Palms

There is so much in the focusing on Palm Sunday without skipping forward to the Passion that invites us into a more robust Holy Week. Mostly because the distinction of the Triumphal Entry serves, not as a contrast to the Passion, but is the embodiment of a contrast that is present in both.

The disciples cheering for Jesus at the beginning of the week are not the crowds calling for his execution at the end of the week. This is important to note, especially as Luke describes these crowds here as disciples, which is to say, students following Jesus. A cohort that now likely numbers in thousands, not, as we often assume is twelve. The disciples don’t seek to have Jesus killed, it is the Temple leadership, notably the chief priests and the ones we might describe today as the most evangelical and doctrinally obsessed.

Two other things worth exploring in Luke’s telling here are the pieces that are such obvious opportunities for imagery that are so easily glossed over:

- the colt

- the stones

I can never resist exploring the possibility that Jesus rides an untamed young horse, and what that demonstrates to the people and to those religious leaders. Reading past sermons below, you’re bound to find this the most consistent theme.

The one I might light to explore in the future, however, is the image of the stones speaking, which comes as a veiled threat from Jesus, but also speaks to how stones already speak in carved images and words, and how there is real permanence in stone that is fleeting in the human experience.

If we focus on the Passion

I find it redundant to focus on the Passion twice in the week — and may betray a preference when some will do it on Sunday and then Good Friday and then preach the resurrection on Easter — a 2:1 death-to-resurrection ratio. But even so, there is some important resonance in noting what we might not later — perhaps focusing on the trial more than the executing, perhaps.

There are two aspects of Luke’s Passion that are unique to it and essential to understanding what the evangelist is after.

- Jesus must be truly innocent

- Jesus must go through the motions of the sham arrest and trial

While the innocence of Jesus is assured by each of the evangelists, Luke is obsessed with assuring us that he did ZERO wrong. And more importantly, it is a particularly unjust experience. This ensures that Jesus isn’t just morally righteous, but also legally righteous. There is no he said / she said distinction here. He does nothing wrong, never admits to having done anything (”you say”), and is punished by people who want to punish him anyway.

This is important for Luke, not to prove the purity of Jesus so much as the spiritual corruption of the state that would punish an innocent man — an especially evil countenance when they know they have no ground to do so.

Many of us who were raised on cop shows to see the “good” officer who just knows the bad guy has done something and yet can’t prove it. We are trained to assume a moral righteousness as an inherent quality rather than the more neutral truth that these unfounded assumptions lack righteousness.

The Sham

This relates, then, to the second issue worth exploring: that the arrest and trial are unjust, but Jesus must go along with it. Even to the point of orchestrating the whole thing.

In one of the most controversial parts of the gospels, Jesus asks his disciples to take the collected money and buy a couple of swords so they can look like revolutionaries. When the disciples produce a couple of swords because a couple of them are carrying, Jesus says this is enough.

As I have written extensively on this passage, the idea is that there is NO WAY in Jesus’s mind that ANY of his followers would be carrying swords. That’s why they are supposed to go buy some. This is important for the reader to recognize the inherent innocence of Jesus and the disciples because they aren’t the ones bringing weapons to the protest. Except that they are. This represents a way the disciples have undermined the teachings of Jesus by not trusting his love will protect them.

In sparking the arresting situation, Jesus invites the state to choose wisely and to execute justice righteously. They, however, turn to lies, mockery, and abuse instead. The entire Passion narrative is filled, not with justice, but injustice and barbarism, cruelty, and the dehumanizing of an innocent man.

We might be put in mind of the ways Christians have utalized abuse for its own cruel unjust values, from the Crusades to the War on Terror to a present complicity with genocide in Gaza.

If we focus on both / neither

One of the most common traditions in the church is to not preach at all on Palm Sunday, letting the Passion be the word. I’ve never countenanced this approach myself because, as should be clear already, we aren’t reading the whole story anyway. And there is much in our tradition which undermines our ability to learn from the gospel this way, such as a long history of anti-semitism.

I also worry about the gloss-over that tries to tell the epic sweep. Not because I don’t think its important (much the opposite, actually!) but because we might struggle resisting the shortcut of overly spiritualizing the story and reinforcing historically problematic takes on the Passion story. Takes such as “humans screwing up” and that “WE killed Jesus,” which is a kind of evidentially true but fundamentally useless take. Much like the teacher that responds to “Can I go to the bathroom?” with “I don’t know, can you?” Actually we all do know! And you’re not addressing the problem!

Among the things to hold tightly to from the Passion, humans killing Jesus may be about number 7 or even something more like 16 in most important things about this story worth remembering. It is so disembodied that we have little to work with here. Do we do this when a human kills another human? Do we dwell on that fact as the central piece of our sense of the human condition — or do we focus on what leads a person to kill? Yeah, exactly.

What’s missing

What’s actually missing from the entire Holy Week experience is a fundamental sense of why it plays out this way. What happens on Monday and Tuesday in the Temple, when Jesus makes a big scene one day and then humiliates the leadership the next day, is where the reader finds the motive. Then, when Judas betrays Jesus Thursday night, we’ve got a sense that the authorities were already looking for a way in.

If we want to help people get the story, we need the whole story. Not a gloss about the nature of people that leans onto a propensity to sin. We need something that matches the moment, that helps us make sense of what our rabbi was up to, and how we might recognize that same character in our own communities.

That’s the work. I’d rather we give it our best effort than pretend the story tells itself.