A look at the gaps in the lectionary.

This week: the gap between Proper 19C and Proper 20C.

The text: Luke 15:11-32.

You know this story.

Even if you’ve never read it, you know it. It’s in your bones and in your imagination.

Artists have mused with it. Writers have cribbed from it. Filmmakers have remade it over and over again.

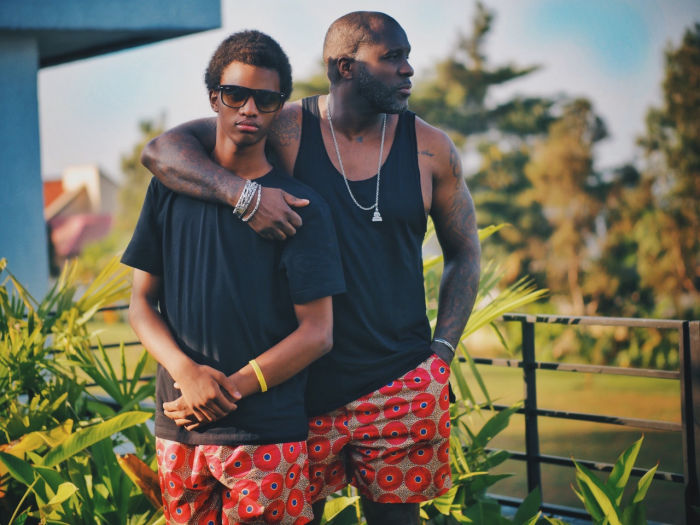

A father forgives and a sibling rejects.

This is the story of fathers and sons, of brothers, and of loss and frugality.

And it is the story of living recklessly and playing it safe.

No story in history has so checked all the boxes at once as this one.

We got this story earlier in the year (Lent 4C).

And I suppose, if there is any other time to deal with this story, Lent is pretty good.

But there’s something about getting this story in its context that really makes it sing.

If we catch Jesus throughout this sequence on the struggle of discipleship, of speaking to the religious leaders about the way they exclude and arrive at this moment when tax collectors and sinners are drawing near to hear him, we can see how bold Jesus’s vision for us can be.

Chances are, we dabbled in this on Sunday, with the preceding parables of the Lost Sheep and Lost Coin. And next week, we’ll move into an even more conflicted and confusing parable in chapter 16. But let’s make sure we give a few moments of attention to what we’re skipping over.

Two Sons

If you’ve read Timothy Keller’s The Prodigal God then you already know that the public imagination gets this parable wrong by half. There are two sons.

Oremus Bible Browser calls this “The Parable of the Prodigal and His Brother,” which is just as telling by what it implies.

The easy division is highlighted at the beginning of the chapter. Because a bunch of sinners come near to Jesus and the religious leaders curl their lips at this. This clearly is a parable for these two groups.

But in our receiving it, we get a different thing. We get a story which reveals the tension between the two. Just like Mary and Martha earlier, we are asked to deal with something that probably makes some of us at least somewhat uneasy.

Think about how easily stories about economics, inequality, and justice are evaluated by conditions of motivation. This, after all, is the fair objection of the elder brother.

- He first gets mad that his Dad forgives his good-for-nothing brother.

- Then he gets madder because his Dad didn’t tell him directly.

- And then its that his Dad is going to throw a party for him!

- And he had to hear about it from one of the help?

So clearly the one son is pissed. And he feels justified in being pissed.

But there’s another reason. The reason that he doesn’t want to forgive his brother. And the reason he is now angry at his father.

What is the incentive to do the right thing now?

To the frustrated one who stayed behind, gave his life to being the good son, all incentives evaporated in an instant.

It’s also why the father’s response unnerves him.

He says

“Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours.”

To the pissed-off son, this sounds like a father not listening to his rational objections. But to the father, the son sounds like a spoiled brat who has learned nothing.

Because “the bad one” isn’t really getting special treatment. This isn’t a reward for past behavior. This killing of the fatted calf and a big party aren’t contingent on behavior at all.

This isn’t something won or something expected. The Dad didn’t give this kind of celebration because it’s Friday night or because the son got good grades at school.

He’s throwing a party because his son was dead to him. And now he’s alive. God has made a miracle and we celebrate that!

Economic morality at the heart of the story.

Moving into the strange parable atop chapter 16, I’m really taken with the ways our economic morality is so built around twin pillars: ownership and the sense of deserving it.

And it strikes me that given what we have just read, the Lost Sons parable deals precisely with this.

The elder son expresses deep sin, not simply in rejecting his father, but completely misrepresenting his relationship to his own father.

The younger son breaks the heart of his father by leaving, yes, but what kills him is that his son asks for his inheritance. The son is economically killing off his father to receive now what he would at his father’s death.

And yet the elder son takes staying at home in precisely the same way. He treats his relationship to his father as transactional, too. You didn’t do this for me. You didn’t treat me the same. Then when his brother gets a party, he says Where’s mine?

The sin doesn’t come when the elder son walks out on his Dad at the end. It came when the younger son left and the elder began to see his Dad as the bank.

The moral judgment of the elder son, informed in part by the incentive of expectation, is just as alienating to him and to his relationship to his father as his brother’s.

Their dislocation isn’t only geographic. It represents their relational dislocation.

At the beginning the younger leaves, killing himself off from his Dad. But he comes back. So they are reunited. The relationship is restored!

But at the end, the elder son rejects his inheritance itself over the father’s mercy! He would rather give it up rather than share it with one he still considers the riff-raff.

Of Mercy

So this parable of deep moral, economic, and relational behaviors precedes a parable about a dishonest manager. A parable which, on the surface, seems to support dishonesty in the service of selfishly making friends.

But does it?

“You cannot serve God and wealth.”

Which does the elder son serve?

In the end, is it even either?

Relating these two parables may help us differentiate our own moral economic compass.

Further Reading on the Lost Parables

Being Lost and Being Found – how Jesus reimagines a God of love

A Story of Two Lost Sons

The parable you never knew – the lost coin and making change

Learning to change from the prodigal sons

Too Good