It is far easier to find God at work in our history than in our present.

There God is all pulling the strings and making things happen. Here? Well, that depends on your theological proclivities.

Our theologies have grown out of problems and the choices we make in response to them. Much like we’re doing in this series. Much of it around the question I mentioned earlier: Why do bad things happen to good people? For us, we wrestle with Providence: the question of how active God is in the world.

Because the question of bad things happening to good people isn’t just about the good/bad dynamic. It’s more about the “why do”. Why do bad things happen?

This question, at its root supposes that God is either connected or disconnected. But both suppositions demand we find God responsible for the course of the world; through action or ignorance.

A question with two options.

Immanent or Transcendent?

Tradition divides God’s activity into two qualities: immanence and transcendence.

If we believe God is present and active in the world, we say God is immanent.

Or if God created the world and let it go, stepping back to watch what happens next, we say God is transcendent.

The contours of both beliefs are fascinating and reveal a great deal about the way we see God. And about the way we see humanity.

One choice leads to another. And then another. And another. Choices about God, of scripture, of revelation and tradition. All building to form a theology.

But this one, the choice between immanence and transcendence, is big. And it is not as readily divided as we like to think.

It isn’t a Left / Right division

Unlike many other ways we divide up our faith into liberal or conservative, this one doesn’t. People who believe in an immanent God who acts in our world can be found in many liberal and conservative circles. As do many who believe in a transcendent God. Our tendency to shoehorn all theology into two camps which just so happen to overlap with two political parties isn’t helpful here (if it ever is).

Immanence and transcendence don’t break down along political or denominational lines. It isn’t a left / right division. But it has a huge impact on how we relate to our faith, our relationship to God, and to our actions in the world.

For it is the difference between God being here! And God being way out there somewhere!

Immanence and transcendence is but one factor. It locates God. But it doesn’t speak to how or when God will act. That’s a whole different factor.

Is God Good?

This is the other question we need to ask when dealing with Why bad things happen. We don’t only need to know if God is around to act. We need to know if God does. And when. And how.

This is why we look at our history first. So we can see how God has been involved in our past. And to name the values God has expressed in word and action.

This is also how we decide what to make of both action and inaction.

People of faith have long wrestled with the ethics around direct action. They also have wrestled with inaction and actions by others on our behalf. It seems we often overvalue the ethics of direct action and undervalue the ethics of inaction or indirect action.

In the case of a tragic event, we argue the former is horrible and “we couldn’t help” the other two. A convenient excuse.

Each Sunday, we make our confession for all three.

So understanding the Why requires that we explore good.

But these two investigations leave me feeling even less satisfied. Because our understanding of an ethical act of good by an immanent God reveals something of a false choice.

If being good requires God to intervene to stop a great tragedy (like the Holocaust, for an extreme example) then we are setting a philosophical trap. Like the question of God making a boulder too heavy to lift, it is not logic, but a riddle. One designed to force us into a false choice based on what we know.

And how we want God to be.

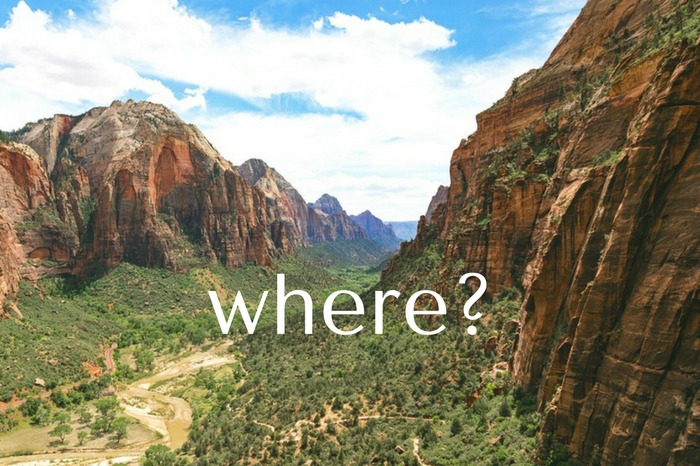

So Where Is God?

If you’re thinking this is all just theoretical mumbo jumbo and mental gymnastics, then you’re right. It’s a mess we create. But we do it because it’s hard to get to the simple response without wrestling with the more difficult.

In the Exile, the faithful people had to look for God in a new place. Jesus brought the same message of God coming in a new way. So did the fall of Rome. And the Great Schism. And the Great Reformation. So did the Holocaust.

Where is God in this?

The answer doesn’t come when we’re on top. When we’re riding high. We assume God is in that.

But where is God at the lynching tree or the gas chamber?

And what so many attest to is this: God is hanging from that rope and being choked by gas, amid our brothers and sisters.

God is with us. And all these other questions about God’s ability or an ethical framework which requires God to intervene don’t match our history or our experience or even Jesus’s teaching.

The choice we make to locate God isn’t hollow philosophy and logic puzzles. It must instead reveal a God worth believing in.

And how we locate ourselves in the world will best determine whether we’ll find God there.

* * *

This is from a series on Choices. Check out more choices we’re invited to make!

Comments

2 responses to “Dude, Where’s My God?”

[…] we’ve been dealing with the nature of God, and have wrestled with the question of providence, how God works in the world, we need to start asking ourselves how active is […]

[…] vision of faith seems much like picking one side of a riddle and then developing a theology around justifying that […]