One need not pray in another person’s language The language of the King James Bible and the 1662 Book of Common Prayer is not ours, it is theirs. It doesn’t define church for me; it defines 17th Century English church. And it is alien to the 21st Century North American church.

I have a devoted Rite I group at St. Paul’s that loves to worship in this alien language. I love them and support them by leading worship in an alien language. Yet, these aren’t our words. And that is significant.

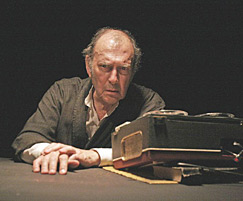

When we worship, we are lifting up our thoughts and prayers to GOD. When we do so in community, we do so in a common language. For many this is the very reason why old church language is essential. I get that. I’ve even made that argument myself. But not any more. I don’t treat our common prayers as if it were Shakespeare and our common worship as if we were reciting Shakespeare. That is placing the style of communication before the substance—while I often find the style to be a barrier to the substance. Instead of recognizing the majesty of Shakespeare’s work in itself, we are imposing something about the style of communication upon the play-going audience. Imagine if we demanded every playwright and poet would mimic his style. Tony Kushner, August Wilson, and Harold Pinter would have rebelled from such an expectation anyway! Many of the greatest plays of the last century would have moved to the streets and low-rent theaters where (gasp) people interested in plays would actually go experience them. In many ways, this is what is actually happening all over the church world. People are leaving stuck institutions and finding places in which “real” worship can happen.

If language is a heavy part of our means of communicating the Good News, why obstruct that communication with out-dated language, or worse, communicate our stylistic desires for comfort and familiarity over the challenging, transforming Good News shared creatively and passionately from within?

Leave a Reply