In the Premodern world, humanity was led by “the divine right of kings,” in other words, authority was bestowed upon a singular human authority from a divine source.

In the Modern world, humanity was led by singular representation. Authority was bestowed on an individual to represent the people, either through fiat or election.

The Enlightenment shook the world and transformed how we would come to understand authority; however, one thing remained the same: singular authority. We only saw one vision of leadership, which was like a pyramid with a pointy tip–and only one man could be at its top. In this way, it didn’t matter what kind of leadership it was or how a leader came to power. Monarchies, military dictatorships, democratic elections (rigged or not), it doesn’t matter when the end result is one person that has power over others.

We are infected with the belief that leadership is singular and that responsibility for groups come from one individual. We believe that groups cannot be held responsible and that it all comes down to the guy in charge. This is not a contagion, but a mutation.

In the Postmodern world, humanity is increasingly led by a network of the people collected, rather than represented by individuals. We know this as grassroots leadership in many parts of the world and groupings of people have been promoting this revolutionary leadership style for decades. It has only become more relevant to those stuck in a modernist framework as it has become increasingly popular and powerful. The rise of social media, from Facebook to Twitter, is proof of the power, not only of innovation or of technology, but of the rise of grassroots leadership itself.

This isn’t dogmatically destructive anarchy or rudderless ships or some other metaphor for the absence of leadership, but a prescient form that takes the uncontrolled id out of the equation–that constant individual pursuit of power–and the community’s subordination to such a figure.

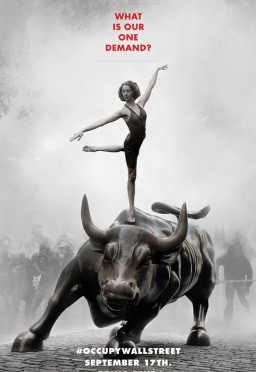

The rise of the network leadership model is a principle driver of emergence–both the theory and the emerging church movement–in which the group bears responsibility for the fruits of its faith, rather than collected individuals or the charismatic leadership at the top of the pyramid. The Occupy Wall Street Movement (#OccupyWallStreet, #OWS) is such an example of network leadership. So there is no wonder the media has such trouble with covering it: they themselves are operating with the wrong assumption.

That assumption, of course, is that one person has to be in charge, or at the very least, one person has been responsible for casting the vision for the people. One man that rides forward like William Wallace and declares that the enemy may take their lives, but not their freedom! That one man must be responsible. Not necessarily.

This is an erroneous assumption. It is a fundamentally corrupted view of the world. We don’t need ecclesiological fascism: one ruler with many followers.

We need to be the leadership together.

The obvious fallacy of “traditional” leadership is found in its devotion to not only physically male representation, but a masculine gendered one. The alternative to this isn’t simply the elevation of women (which I support), but the elevation of the whole community to leadership.

Most of the criticisms of the Occupy Movement’s lack of “specific goals” or “unified vision” bear the hallmark of modernist leadership principles: one man responsible for the many. But the true hallmark of democracy is shared leadership. That each takes not only responsibility for themselves, but their neighbors. At the same time, they show deference to the others who are doing the same.

See, this has nothing to do with purity of message, organizational structure, or other concerns for marketing the modernist leadership paradigm. It has everything to do with creating together a more democratic, more honest relationship to our leadership.

I have seen no stronger example of how the church of the future operates than what has been going on at Liberty Square and popping up all over the country. This is the vibrant, organic church we yearn for. And the only thing stopping us is our own artificially narrowed sense of ecclesiology.

Leave a Reply